The following article was written in the week of the 19th-23rd of September 2022. Due to Substack’s publishing limitations, the article is broken down into 6 independent parts.

The events that unfolded in the week after (the 24th-30th of September 2022) made some chart and price data presented here, partially outdated.

The core narrative outlined in the article did not change.

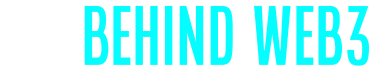

Part 1 - Supply the chains

China’s Zero-Covid policy is putting additional constraints on already disrupted supply chains - and a further tear in the Chinese socioeconomic fabric. For decades now, China has been the world’s production facility. Low production-costs for ‘all things’ the world needs made China a logistically centralised point of origin. For years, western countries outsourced their production to the lands of the far east and imported cheap goods; goods, the local western population could afford. Then Covid happened, and suddenly the supply chain network collapsed and grounded to a halt.

The disruption of the supply chains unveiled the high level of dependence on Asian suppliers, in particular China. Do you remember when national governments had serious difficulties acquiring basic medical supplies, like standard facial masks? In the EU, there was a strong sentiment of “every man for himself”, despite the official ‘European Solidarity’ parole. Planes with medical cargo ordered by an EU country were confiscated, diverted, seized, plundered, and held in customs - by another (EU) country. National borders were re-introduced, and passenger flow was heavily restricted and controlled. Strange times in which paroles like ‘The Might of European Unity and Solidarity’ were shown to be merely a fragile charade for keeping up politically motivated public appearances. These were times in which serious challenges revealed the ‘true colours’ of the EU and its member states.

When the supply (i.e., the manufacturing) of any goods and services is heavily constrained, an unchanged level of demand will lead to higher prices, even when the delivery routes are in perfect shape. But when increased demand meets shut-down production, with non-functioning or unavailable delivery routes and methods, the prices of goods are going sky high. Warehouse stocks are depleted fast, starting with those in our own backyard: local small producers and retail stores.

This has been the main driving force behind the present high inflation, not the Quantitative Easing (QE), often falsely labelled as ‘money printing’, which primarily soars the prices of financial assets. But that is a subject for another time, a subject with much discord between economists.

The unchanged, or mostly increased demand is now surpassing supply capacity many times over. A well-known example is the car industry, where car makers are unable to complete production due to missing parts, often small electronic parts. It was (and still is) common to hear that the estimated delivery time is 12 months or more. The demand for vehicles led to a price surge in secondary markets. At times, used cars were priced as new ones. However, buyers could take possession and drive off as soon as the payment was completed.

The initial supply chain disruption is now prolonged and further exacerbated by China’s Zero-Covid policy and the ongoing war. The war between the U.S. vs. Russia and China.

China’s chips give the U.S. headaches

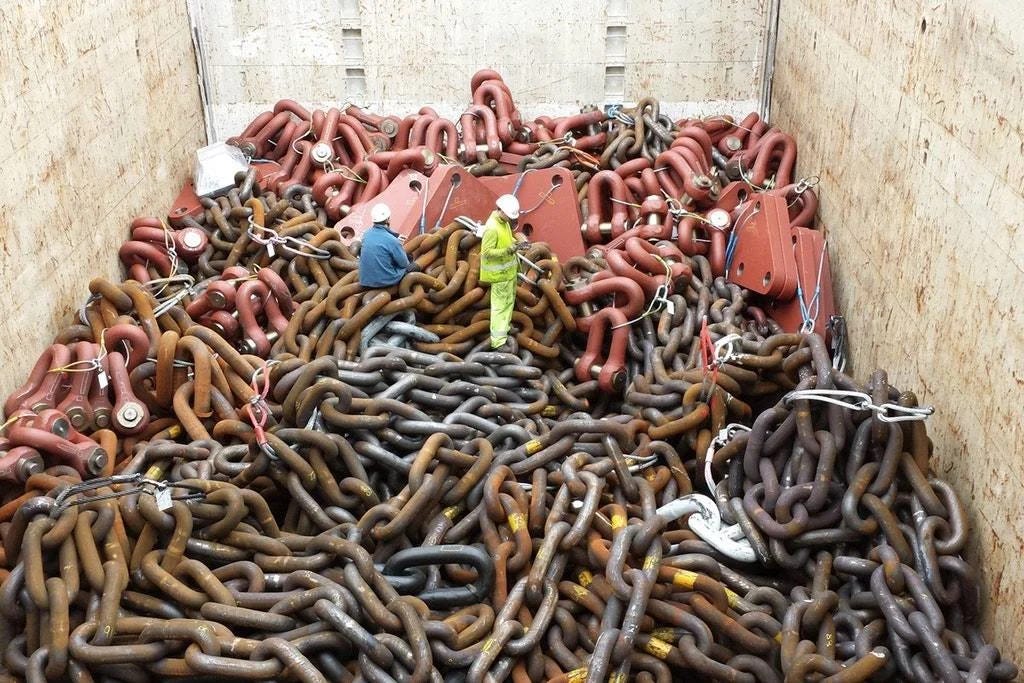

The tensions between these countries have adverse effects on the economies of other countries like Taiwan, Japan, or South Korea. That is where world’s leading microchips and semiconductors manufacturers are located, with production facilities also in China, supplying the U.S. and the EU. Semiconductors are used almost everywhere, like in household appliances, transportation, computer hardware and telecommunications, as well as in modern weapons and missiles. They are of great economic and geo-political importance - and are globally in short supply.

In this context, the existing tensions between China and the U.S. over Taiwan (and its independency) have the potential to escalate further into an open military conflict. Yes, this is nothing new and has been talked or written about a lot for some time now. But it is one of the factors in the current supply chain and economic (inflation) crisis plaguing world trade and economy.

There is a concentrated political effort by the U.S. to prevent any further dependency on Asian semiconductors by developing domestic production capacity. The effort goes even further, leaving China’s goal of self-sufficiency in the microchips industry ideally an unattainable one. The EU is taking similar steps to achieve a lower dependency. You can read more about it in a brief article I published separately here:

The U.S.’ headaches over China’s chips

China’s semi-conductor manufacturer SMIC made a technological breakthrough achieving 7nm (nanometer) production capabilities. This breakthrough makes SMIC the third chipmaker worldwide in the 7nm spectrum. Geo-politically, this achievement is a highly sensitive matter, which doesn’t make the U.S. happy about it. Earlier, the U.S. introduced a ban on Dut…

Sanction me gently

Concerning the ongoing war, Europe is mostly caught in between, but not neutral, and not entirely innocent, or without its own contribution to the detriment it found itself in. And the EU’s leadership is still taking it up a notch, as last week’s von der Leyen speech shows: “And I want to make it very clear, the sanctions are there to stay”. There are over 11,000 different sanctions against Russia alone, imposed by the U.S. and the EU. And there are many sanctions against China as well. Sanctions that mostly hurt the EU in every aspect possible, less so the U.S.

Generally, sanctions mean that domestic companies under the sanctions-imposing government are prohibited from doing any type of business, trades, or financial transactions with the sanctioned nation, subject, or entity. It often goes beyond that, extending this prohibition onto third-party foreign countries’ businesses and entire governments.

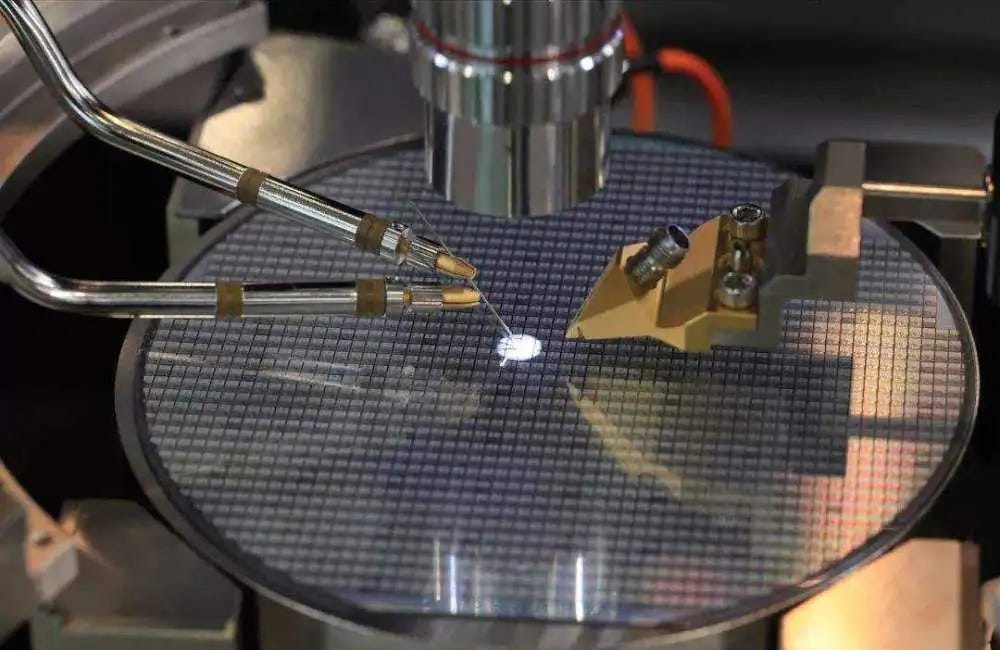

Sanctioning a major production facility many nations rely on for their goods, has negative consequences for many, even indirectly involved economies. It represents an entirely new level of negative effects when broad sanctions are imposed against vital commodity and raw materials suppliers, which rightfully so have great systemic importance for world trade. Yes, we are primarily talking about Russia here. Natural resources are abundant in Russia and are supplied to the entire world. The below illustration shows the share of commodities exports by destination.

Seeking to impose an arbitrary will and control on big, crucial market players such as Russia and China, will inevitably cause negative economic consequences. One of the consequences is the high inflation we now have across the globe.

Any manufacturer is a supplier of goods or products and is himself dependent on raw materials or commodities that are provided by commodities suppliers. A frictionless supply of commodities enables the production and delivery of what a buyer ordered. If both said suppliers are choked, customers needing their goods will not get any, save what is in stock already, until that too, runs out. In modern logistics systems, just-in-time delivery is a way of keeping costs low, which is associated with low warehouse stock. It frees up bound capital that can be used otherwise. A drawback of this approach is when low warehouse stock is gone, the demand remains (high), and there is no access to manufacturing or delivery routes. Or, there is, but businesses are not allowed to access them, because their local or foreign government says so. There are even self-sanctioning companies out of fear of loss of reputation. We get the same result - no supply.

Lacking (optimal) alternatives, what else can be done?

At this stage, profitable arbitrage opportunities arise. Different actors apply creative methods to extract profits and take advantage of the circumstances. There is a mixture of all flavours of middlemen, smugglers, reinstating back channels, repackaging, renaming, and other tricks to circumvent any direct, official trades and payments between sanctioned, unsanctioned, and sanction-imposing entities. Whilst a certain official narrative is upheld in the public; behind doors, through back channels, high-priority goods will still be supplied. There is an absolute necessity of protecting local industries and societies from collapsing. Politicians know this, we can safely assume. A ‘by-product’ of sanctions-circumventing practises is: much higher prices for the end user. Hello, inflation!

As private consumers, we may order something online, maybe on Amazon. It says four weeks delivery time. We might think to ourselves: that is unusual; last year the delivery took only five days, costing only a third of today’s price. We scratch our heads and wonder what is going on. Maybe we will shrug it off and order anyway, and not give it any more thought.

But as a local manufacturing company, we need access to reliable sources of both raw materials and energy alike. For EU companies, both are hard to come by these days or are brutally expensive.

Why? Because of broken (global) supply chains, but mainly because of the EU’s own sanctions against Russia.

“Yes, hello, this is John from John’s Bakery. I would like to order seven bottles of energy, please. My cookies are in the oven already, when can you deliver?”

-- continue reading Part 2 here:

Chips, oil, and gas - What’s cooking?

Part 2

The following article was written in the week of the 19th-23rd of September 2022. Due to Substack’s publishing limitations, the article is broken down into 6 independent parts. The events that unfolded in the week after (the 24th-30th of September 2022) made some chart and price data presented here, partially outdated.