Part 6

The following article was written in the week of the 19th-23rd of September 2022. Due to Substack’s publishing limitations, the article is broken down into 6 independent parts.

The events that unfolded in the week after (the 24th-30th of September 2022) made some chart and price data presented here, partially outdated.

The core narrative outlined in the article did not change.

Part 6 - Food for food

Let’s briefly look at the looming food crisis.

In the last part, we touched upon the correlation between gas supply and fertiliser production. Food crops yield is lower without food for food. Farmers can achieve higher harvest output on a same-sized piece of farmland if they provide nutrients to sown crops. Poorly fed plants will develop poorly, die or give nothing to harvest. A subject on fertilisers is not about boosting farmers’ profit margins, but about the bigger picture and the food stock necessary to feed entire nations around the globe.

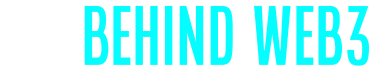

In 2021, Russia was the largest exporter of agricultural fertilisers worldwide, with China coming in as 2nd.

Gas is a crucial raw material used for fertiliser production. The European gas crisis has already turned into a big fertiliser crisis for European agriculture, see the illustration below.

In the above illustration, we can see which EU production facilities are currently operational and with which current output, as a share of total yearly production capacity. Noticeably, the operational status shows either shut down, or curtailed, or temporarily halted, or reduced.

The gas crisis forced Azomures to shut down its production, affecting 75% of Romanian farmers. Azomures is a Romanian fertiliser maker and the EU’s largest industrial gas user. Just a few weeks earlier, Norway’s Yara International cut its ammonia production down to one-third. With Azomures now halting its production, close to 70% of the EU’s fertilizer production is shut down as well.

As a part of Germany’s PPI numbers, which were mentioned earlier, the prices of ammoniac are up 175.9% for Aug-22 vs. Aug-21. This is a crucial price development to observe because ammoniac is used to produce fertilisers…

Potassium is another key ingredient; it is one of the three main nutrients used in fertiliser production.

In March 2022, a sanction package was approved by the EU targeting 100% of imported potassium chloride. These sanctions are imposed on Belarus, for its support of Russia. In Belarus’ underground deposits, potash - a potassium-rich salt - is mined. In 2020, the EU consumed 85% of the total imported potash, based on data from FertilizersEurope. Potash coming from Belarus had an average share of 27% for the period 2018-2020.

The sanctioned large-scale fertiliser producers, Russia and Belarus, together account for over 40% of potash exports - worldwide!

This story about the fertiliser situation demonstrates how highly important this issue is as it relates to global food security, causing spiralling food costs, and likely triggering a food crisis. Many countries have national, large-scale food reserves to dampen the negative effects of any short-term changes in food supply, e.g., due to lower domestic production or supply-chain interruptions. Saving for expected and unexpected events is a core purpose of any emergency or rainy-day fund, no matter what is being saved: money, water, gas, food, medicine, blood, etc. In general, it is a part of risk and crisis management, especially so if there is evidence of expected negative events with high occurrence probability and extensive impact.

A few basic and strongly simplified, yet key questions come to mind:

What is the storage capacity? How much is already in stock, how much is missing? How much can be afforded? How much can be obtained, and when? What is the pessimistic expectation for the expected event’s duration? Based on that, how long would the storage stock last?

When an expected event occurs, its duration and intensity can make all the difference. It provides the final answer on how well emergency or rainy-day funds perform.

Bread, noodles, muffins

Wheat. It is used to make a lot of different food products like cakes and snacks. But most importantly, milled wheat is used to make bread, the most basic food millions of people survive on. Russia is the largest wheat exporter worldwide for 2021. Ukraine is the 5th largest, and together with Russia accounting for nearly one-third of the world’s wheat supply (!) Another major wheat exporting country is Romania, coming in 9th. This will likely change as 75% of the fertiliser supplied to Romanian farmers comes from Azomures.

In the below illustration, the importance of Russia’s and Ukraine’s cumulative grain exports cannot be overstated. Wheat is part of ‘total grain exports’ data, with barley, soybeans, rice, and maize also included in the ‘grain’ index basket (International Grains Council).

Since December 2021, there are many reports regarding the grain hoarding practises by China, especially of wheat and corn. Based on data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), it is expected that China will have 51% of the world’s wheat reserves, 69% of maize, and 60% of rice. These silo stockpiles were projected for the first half of the crop year 2022. The alleged systemic hoarding relates to the last five years, and it did not just start due to the Ukraine invasion in February this year. However, Ukraine was a major supplier of corn to China. Now, China is making very large food purchases on the international market in light of the worsening wheat crisis, according to USDA data from April and May 2022, and is expected to continue doing so.

Many critics of China’s grain and food accumulation highlight the rising food prices, which get a tailwind from Covid lockdowns, constraint and broken supply chains, general inflation, and the ongoing war.

Finally, making a sandwich

The September 2022 data from Eurostat depicts a significant soaring in bread prices across EU member states. A staggering 18% annual price change for bread (as a basic food item) is in accordance with all presented facts we have discussed so far, and thus comes as no surprise.

The increased food prices are just one of the outcomes of the events we slightly examined in this article; the events that are still unfolding with a spill-over effect.

Now, let’s move on to the closing remarks.

-- continue reading the Outro here

Chips, oil, and gas - What’s cooking?

Last one: Outro! The following article was written in the week of the 19th-23rd of September 2022. Due to Substack’s publishing limitations, the article is broken down into 6 independent parts. The events that unfolded in the week after (the 24th-30th of September 2022) made some chart and price data presented here, partially outdated.

or

Start over and read from the beginning: Part 1

Chips, oil, and gas - What’s cooking?

The following article was written in the week of the 19th-23rd of September 2022. Due to Substack’s publishing limitations, the article is broken down into 6 independent parts. The events that unfolded in the week after (the 24th-30th of September 2022) made some chart and price data presented here, partially outdated.